The Seattle Times | By Sandy Doughton | Feb. 24, 2023

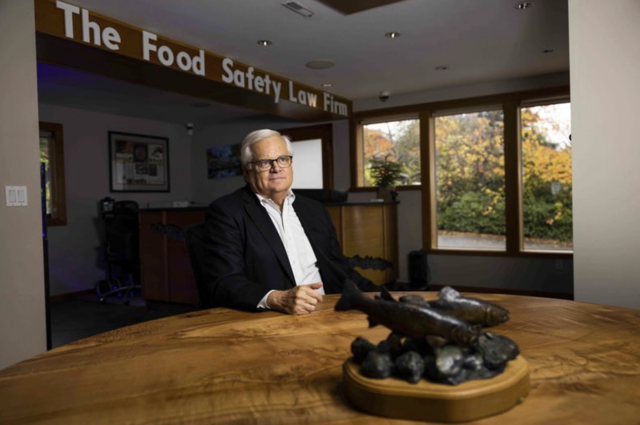

Seattle attorney Bill Marler will be featured in an upcoming Netflix documentary about the 1993 Jack in the Box food poisoning outbreak. Thirty years later, Marler is still suing companies for selling food that makes people sick. He’s shown here at his home office on Bainbridge Island. (Daniel Kim / Seattle Times)

THE CHILDREN STARTED showing up at Western Washington emergency rooms in early January 1993, desperately sick with internal bleeding, seizures and kidneys on the verge of collapse. As parents held vigil in ICUs and doctors battled to keep their young patients alive, investigators zeroed in on a common denominator: undercooked hamburgers from Jack in the Box restaurants.

Like most people back then, Seattle attorney Bill Marler had never heard of the oddly named strain of bacteria — E. coli O157:H7 — identified as the culprit. He spent hours cramming in the University of Washington medical school library before filing one of the first lawsuits. Marler had no idea his life was about to change, along with those of the families caught up in what was, at the time, the most shocking food poisoning outbreak in United States history.

Four children died. More than 700 people — most under the age of 10 — were sickened across five states. Many never fully recovered.

The outbreak was a turning point for food safety, leading to some of the first significant regulatory reforms in nearly a century. It also was pivotal for Marler, who was less than five years out of law school and chafing at what felt like a dead-end job. He and his colleagues maneuvered themselves to the top of the E. coli litigation scrum, winning $50 million in damages for nearly 200 victims.

Marler never expected to build a career out of bad food. But 30 years later, he’s still at it. From salmonella-tainted cantaloupe to listeria-laced lunchmeat, Marler Clark — which bills itself as The Food Safety Law Firm — has represented victims of every major foodborne illness outbreak in the United States.

Seattle attorney Bill Marler got his start in food safety litigation during the 1993 Jack in the Box E. coli outbreak. Undercooked hamburgers sickened hundreds of people and killed four children. (Daniel Kim / The Seattle Times)

“Everybody knows if you have a food poisoning problem, that’s who you go to,” says Marion Nestle, author and food policy expert at New York University. “If I were a food company, I would be terrified of Bill, because he usually wins.”

With his flair for publicity, Marler also has been a major force in raising awareness of the dangers posed by unsafe food, she adds. “He always puts the victims first.”

But litigation is a blunt instrument for change, Marler tells me at the firm’s downtown Seattle office in mid-January. The suite’s exposed brick walls are decorated with framed clips from The New York Times, USA Today, Forbes and trade magazines, all featuring Marler and the people he’s represented.

His team has collected more than $850 million from food companies, of which Marler Clark banks about 25%. And the outbreaks keep coming.

ACCORDING TO THE CDC, 1 in 6 Americans — 48 million people — is poisoned by food every year. Of those, 128,000 wind up in the hospital, and 3,000 die.

That’s good for business but bad for public health, says Marler. While he still enjoys the thrill of a juicy lawsuit, these days, he spends almost as much time pushing for more effective regulations to prevent people from getting sick in the first place.

“I’ve seen so much death and trauma,” he says. “I’ve been in ICUs with families when they removed their child from life support. If that doesn’t make you want to do anything you can to avoid that happening to another family, then you need to reassess who you are.”

Cheray Jefferson gets a checkup at Seattle Children’s Hospital a year after she was hospitalized with an E. coli infection from contaminated, undercooked hamburger at Jack in the Box in early 1993. Cheray lost part of her colon and suffered organ damage. (Betty Udesen / The Seattle Times)

After being released from the hospital, Cheray Jefferson is carried into her home by aunt Shamone Jefferson as her father, Kelly Jefferson, looks on. “I just want her to be like she was before this,” he said. The little girl suffered organ damage from E. coli contaminated hamburger in 1993. (Betty Udesen / The Seattle Times)

Michael and Diana Nole, who lived in Tacoma at the time, visit the grave of their 2-year-old son, Michael, who was the first child in Washington to die from eating undercooked, bacteria-tainted hamburger at Jack in the Box in 1993. (Betty Udesen / The Seattle Times)

Marler’s advocacy efforts include speaking to food industry groups, where his favorite line is: If you don’t like being sued, clean up your act and put me out of business.

Skeptics roll their eyes and point out there’s an element of self-promotion to almost everything Marler does. But he’s serious about making food safer.

His latest crusade is to get salmonella out of chicken in the same way regulators and processors virtually eliminated E. coli in hamburger after the Jack in the Box outbreak. Or, as Marler puts it, “I’m the guy trying to get chicken s*** off chicken.”

In May, the U.S. Department of Agriculture rejected his petition to make it illegal to sell poultry contaminated with more than two dozen toxic strains of salmonella, which wind up on carcasses mostly via fecal contamination. But Marler’s not giving up. In January, he sent a letter warning the agency it’s on shaky legal ground, and hinting at possible litigation.

Marler hopes the issue will get a boost from a Netflix documentary scheduled for release later this year about the Jack in the Box outbreak. (The date is still uncertain.) It’s based on writer and producer Jeff Benedict’s book “Poisoned,” which was republished in January. The book, which The New York Times called “completely gripping,” tells the behind-the-scenes story of Marler and his most famous client — a 9-year-old Redmond girl named Brianne Kiner.

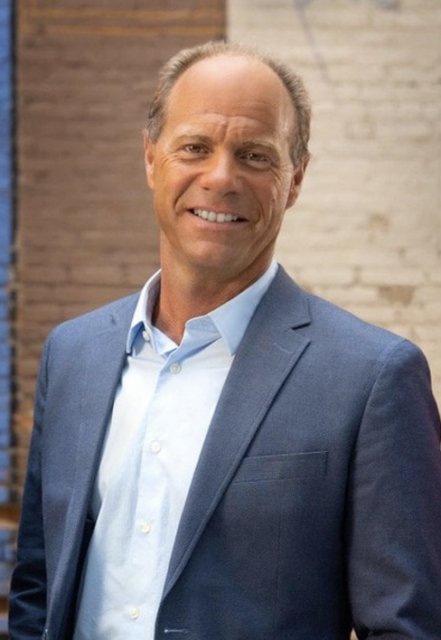

Jeff Benedict initially set out to write about food poisoning linked to peanuts but became fascinated with Bill Marler and the Jack in the Box outbreak. He couldn’t find a publisher for “Poisoned,” so he published it himself in 2011. The book was reissued this year by Simon & Schuster and is the basis of an upcoming Netflix documentary.

Author Jeff Benedict, known for his books on Tiger Woods and the New England Patriots, was so fascinated by Bill Marler and the 1993 Jack in the Box food poisoning outbreak that he self-published “Poisoned” in 2011 after publishers rejected it. The book was reissued in January and is the basis of an upcoming Netflix documentary. (Avid Reader Press / Simon & Schuster)

Jeff Benedict’s 2011 book about the 1993 Jack-in-the-Box E. coli outbreak and Seattle attorney Bill Marler’s fight for the young victims and their families, was reissued in January to coincide with the Netflix documentary.

AFTER A PANDEMIC, three decades of mass shootings and countless food recalls, it’s hard to appreciate the gut punch in 1993, when children started dying and falling ill from the simple act of eating a hamburger. Even before social media, news coverage was national and nonstop. Angry, grieving parents told their stories on the “TODAY” show and welcomed cameras into hospitals, where their children lay unconscious, attached to tubes.

The public was outraged to learn Jack in the Box didn’t cook burgers to 155 degrees, as Washington state law required. The USDA admitted it was perfectly legal for meat stamped with its seal of approval to be teeming with bacteria.

“I remember thinking: ‘This is the United States of America in 1993. How can this be happening?’ ” recalls Darin Detwiler.

He was living in Bellingham then when his 16-month-old son, Riley, came down with bloody diarrhea — a classic symptom of E. coli infection. The family had scrupulously avoided hamburger and Jack in the Box. But a wave of secondary infections was underway. Riley picked up the bug from a child at day care who had eaten at the chain.

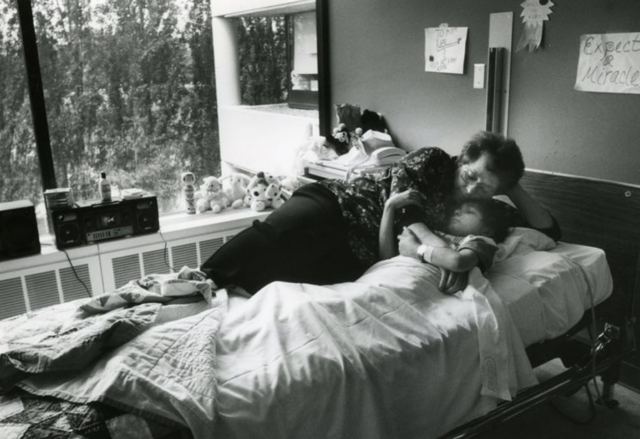

At Seattle Children’s Hospital, Detwiler tried to cradle his son among the oxygen lines and monitors. Surgeons removed most of Riley’s colon but couldn’t stem runaway organ failure. Riley died on Feb. 20, 1993, the outbreak’s final fatality.

Darin and Vicki Detwiler sit in the hospital with their 16-month-old son, Riley. In early 1993, the youngster contracted E. coli bacteria from another child at his day care. Riley was one of four children who died in the Jack in the Box outbreak. Darin Detwiler became a food safety professor and advocate after his son’s death. (Ron Wurzer / The Seattle Times, 1993)

“He was just taking his first steps. Just saying his first words,” recalls Detwiler, who went on to become a food safety advocate and professor at Northeastern University.

Doctors called Brianne’s recovery miraculous. She was in a coma more than 40 days and developed diabetes from organ damage. When she regained consciousness, she had to learn to walk and dress and feed herself again. Her release from the hospital after nearly six months was front-page news across the country.

Nine-year-old Brianne Kiner was the most profoundly injured survivor of the 1993 Jack in the Box food poisoning outbreak. The Redmond girl spent 40 days in a coma, and doctors didn’t expect her to survive. Bill Marler represented the family and won a $15.6 million settlement. (Jimi Lott / The Seattle Times, 1993)

Suzanne Kiner comforts her daughter, Brianne, in her hospital room after a morning of rehabilitation exercises. Brianne almost died from an E. coli infection that ravaged her organs. She spent more than five months in the hospital and had to learn to walk and talk again. (Teresa Tamura / The Seattle Times, 1993)

Before she left the hospital after more than five months, Brianne Kiner had to learn to walk again. Here therapist Kristine Shakhazizian helps her up stairs at Seattle Children’s Hospital. The Redmond girl was 9 in January 1993, when she ate an undercooked hamburger at Jack in the Box contaminated with E. coli bacteria. (Teresa Tamura / Seattle Times, 1993)

Marler negotiated a $15.6 million settlement from Jack in the Box and its parent company for the youngster and her family, setting a state record.

He also mobilized his clients to talk to the media and testify in congressional hearings to demand changes in food safety laws. Other parents whose kids were killed or sickened by E. coli created the advocacy group Stop Foodborne Illness. And for once, the government was listening.

NEWS OF THE Jack in the Box outbreak broke two days before Bill Clinton was inaugurated. One of his first presidential events was a televised town hall where he fielded questions from the public and spoke with Detwiler and his then-wife. The fledgling administration made it a top priority to revamp the USDA’s food safety program.

“The time had come, and the public was expecting change,“ says Michael Taylor, who was recruited by Vice President Al Gore to do the job. “I had the political winds at my back in a big way.”

When Taylor took over at the Food Safety and Inspection Service, federal inspectors did not test meat for microbes. The agency’s official position was that processors and slaughterhouses had no responsibility for pathogens in their products, even though contamination from feces and gut contents was widespread. Consumers were supposed to know how to prepare meat to kill the bugs — though the industry opposed warning labels or cooking instructions.

Haunted by meetings with parents who lost children, Taylor set out to flip the department’s mindset from serving industry to protecting consumers. His first step was to declare E. coli O157:H7 an adulterant, making it illegal to sell contaminated ground beef. The USDA also mandated safe handling labels and required producers to develop plans to prevent and test for pathogen contamination.

“The industry could no longer point to the consumer and say, ‘It’s on you,’ ” Taylor says. “They had to take responsibility for the safety of their product.”

The American Meat Institute and other organizations sued, and it took several years to implement the E. coli ban. But once it kicked in, it was like flipping a switch.

“Between 1993 and 2002, 90% of my law firm revenue was E. coli cases linked to hamburger,” Marler says. “I still have an occasional case, but those outbreaks essentially disappeared.”

Most of his work now involves leafy greens and poultry.

WHEN MARLER STARTED speaking to food industry groups, people would sometimes walk out or boo. Many considered him a bottom feeder, and some said so to his face. But he’s earned a grudging respect over the years.

Last month, Marler, Detwiler and Taylor were among 16 people recognized by Quality Assurance & Food Safety magazine for their work over the past 30 years. “These people have persevered where their message was often unpopular and expensive, and they managed to truly impact our world,” says the publication.

Also on the list is Dave Theno, who is credited with saving Jack in the Box by transforming the company into a food safety leader. Marler grilled him without mercy during depositions, yet the two became so close that Marler spoke at Theno’s funeral.

Wisconsin-based food industry lawyer and food safety consultant Shawn Stevens has faced off against Marler in at least 100 cases. When discussing Marler and his tactics in presentations, Stevens used to show a cartoon of a lawyer chasing an ambulance. Now, he and Marler share the stage at conferences, both urging companies to produce safer products and warning of the consequences if they don’t.

“I often say it would be malpractice to sit down with a client and not mention Bill Marler,” Stevens says.

News articles detail the record-setting $15.6 million settlement Bill Marler won for Brianne Kiner and her family. The 9-year-old Redmond girl nearly died in the 1993 Jack in the Box food poisoning outbreak caused by undercooked hamburgers. (Daniel Kim / The Seattle Times)

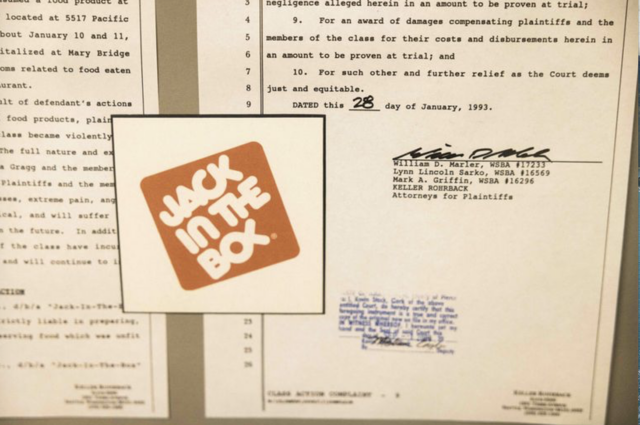

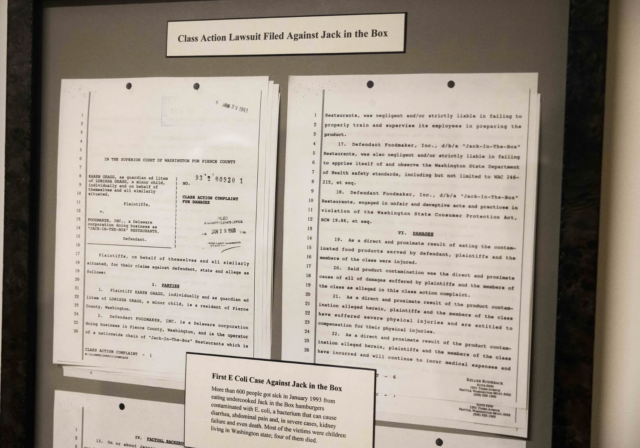

The original complaint Bill Marler filed against Jack in the Box’s parent company on Jan. 28, 1993, hangs in his Seattle office. Marler and his colleagues went on to win $50 million in damages for 200 clients sickened by undercooked hamburgers contaminated with toxic E. coli bacteria. (Daniel Kim / The Seattle Times)

This is original complaint Marler filed in January 1993 against the parent company of Jack in the Box. The fast food chain’s undercooked hamburgers sickened more than 700 people and killed four children. (Daniel Kim / The Seattle Times)

When Congress was debating food safety legislation in 2009, Bill Marler distributed T-shirts with this design to lawmakers and staff, challenging them to put him out of business. (Daniel Kim / The Seattle Times)

Food Safety News, an online publication Marler founded in 2009, has nearly 50,000 subscribers and provides the type of granular coverage it’s hard to find anywhere else. He’s a prodigious blogger, dashing off entries late at night or during flights, and taking jabs at companies he’s suing and policies he doesn’t like.

A few years after the Jack in the Box outbreak, Marler successfully petitioned the USDA to add several additional strains of E. coli to its ban. He lobbies hard for food safety legislation, meeting with lawmakers and sharing heartbreaking stories, such as the toddler in British Columbia left blind and brain-damaged by E. coli in romaine lettuce, or the Las Vegas mother who ate a spoonful of contaminated cookie dough and suffered years of hospitalization and surgeries before dying from complications. Marler also foots the bill for clients to testify in person.

He even applied for the USDA’s top food safety job during the Obama Administration, when he was still more loathed than admired by the food industry. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack essentially said: “You’ve got to be kidding.”

DETWILER CONTINUES TO RECOUNT his son’s death at meetings and conferences around the world, hoping to inspire change — but is getting discouraged by the slow pace.

“It’s like Groundhog Day for me,” he says. “Three decades of foodborne illness and outbreaks — it really starts to eat at you.”

Detwiler coaches companies and agencies in food safety culture, but only if the CEO and other top officials agree to attend. He’s convinced accountability needs to start at the top, with criminal prosecutions for executives of companies that sell tainted food. Only a handful have been jailed, including the owner and managers of a peanut company where staff falsified salmonella testing results and whose products sickened an estimated 22,000 people.

“It’s amazing how there’s such a lack of consequences for these epic failures,” Detwiler says.

At the Dubai International Food Safety Conference in 2015, Darin Detwiler shared the story of his 16-month-old son, Riley, who was the last child to die in the Jack in the Box E. coli outbreak in 1993. Detwiler became a food safety advocate and educator, hoping to prevent similar tragedies. (Courtesy Darin Detwiler)

Darin Detwiler in 2015 at the White House, where he testified before the Office of Management and Budget in support of expanded safety labeling of meat. Detwiler’s 16-month-old son, Riley, never ate at Jack in the Box but picked up a fatal E. coli infection from another child at a day care facility who had. (Courtesy Darin Detwiler)

Marler’s lawsuits provide some financial accountability, but as an advocate, he’s more focused on regulations.

A ProPublica investigation in 2021 described the U.S. food safety system as “baffling and largely toothless … and ill-equipped to protect consumers or rebuff industry influence.”

The USDA’s ban on dangerous E. coli in meat doesn’t apply to produce, which is regulated by the Food and Drug Administration. The FDA prohibits the sale of salmon and pet food contaminated with salmonella. But under USDA rules, it’s fine for companies to sell raw chicken even if it’s tainted with toxic strains of the bacteria.

Marler targeted salmonella because it hospitalizes and kills more people than any other foodborne pathogen. In rejecting his petition, the USDA pointed out it’s working on a new policy to reduce salmonella illnesses, though details have yet to be spelled out. Last year, the agency declared salmonella an adulterant in one type of poultry: frozen, breaded products such as chicken cordon bleu that are raw, but might be mistaken for cooked.

Some poultry growers squawked, arguing that salmonella is too ubiquitous to ever be eliminated from chickens — the same objection the beef industry raised in the 1990s to oppose the E. coli ban. But this time, major poultry producers, including Tyson Foods and Butterball, have formed a coalition with advocacy groups to work on a solution. Some have started vaccinating flocks against the bacteria.

The next battle will be leafy greens, Marler says. Because they’re eaten raw, there’s no way for consumers to kill bacterial contaminants, like E. coli. The pathogens mostly come from manure runoff and dust from nearby livestock operations.

The Food Safety Modernization Act, passed in 2011, was supposed to tackle the problem by setting standards for agricultural water and requiring farmers to monitor for microbes. But that hasn’t happened yet, and the FDA’s latest proposal requires no water testing.

“I’m not saying it’s easy,” says Marler. “But there are solutions to these unsolved problems. We just can’t seem to get our act together to solve them.”

So people continue to get sick and die from eating from food they thought was safe.

And Bill Marler is still in business.

Sandi Doughton: 206-464-2491 or sdoughton@seattletimes.com; on Twitter: @SandiDoughton