Link to video of this story

INVESTIGATIVE TV | By Chris Nakamoto & Jill Riepenhoff | June 03, 2024

ST. MARTINVILLE, La. — As Annette Martin prepared a salad with Romaine lettuce, she had no way of knowing that it had been contaminated with E. coli.

She, like most other Americans, trusted that the country’s food safety system would keep her safe. But within days of eating that salad, Martin was deathly ill.

The Arizona-grown lettuce sickened 210 people in 2018. Nearly a hundred of them, including Martin, landed in the hospital. Six of them died.

Every year, foodborne illnesses sicken 50 million Americans and claim an estimated 3,000 lives.

Annette Martin is healthy today. But in 2018, she had a near-death experience after eating Romaine lettuce contaminated with E. coli. (Jill Riepenhoff/InvestigateTV/Owen Hornstein)

For nearly two decades, the Government Accountability Office, the government’s watchdog, has implored four presidents and Congress to make improvements to the country’s food safety system and has listed its recommendations as a high priority.

But little has changed. In fact, they even have failed to act on what seemingly is a straightforward recommendation - to study the possibility of a single food safety entity, said Steve Morris, director of food and agriculture at the GAO.

“We think that the government really needs to take a kind of systemwide look at this issue. Bring all the key players together, make sure they come up with some sort of national strategy,” Morris said.

Currently, the food safety system is governed by 15 different federal agencies responsible for the enforcement of 30 laws.

Most of the oversight falls on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. But that oversight, food safety advocates say, is fractured.

“Nobody would set up a food safety system the way we have it in 2024,” said Bill Marler, a Seattle lawyer who has represented hundreds of people sickened by food, including Martin. “From scratch, you would have an integrated . . . operation that had not only food safety but also environmental safety.”

Today, for example, pizzas made at the same factory will have different oversight. The FDA is responsible for cheese and veggie pizzas. The USDA is responsible for those with meat.

A meat sandwich with one piece of bread is governed by the FDA. But if the meat is between two slices of bread, it becomes USDA responsibility.

Both agencies carry some oversight of eggs – one for the quality and the other for the safety.

The USDA is required to be present in every processing plant it oversees every day. Facilities under FDA jurisdiction – some 200,000 in the U.S. - are inspected only every few years.

“There have been, you know, laws that came on the books when you had major outbreaks, for example, in the early 1900s, (with) the creation of new entities and new agencies. And so it was never developed as a whole kind of singular entity, it was kind of patchwork over time. And so that’s kind of where we are right now,” Morris said.

Steve Morris of the Government Accountability Office has been documenting the need for reforms to the U.S. food safety program for decades. (Jill Riepenhoff/InvestigateTV)

In addition, state and local laws muddy the issue, too. For example, not every state reports all major foodborne illnesses – including one that led to deaths of infants after drinking formula - to the federal government, InvestigateTV has found.

But if no action is taken, Morris said, the status quo will remain, and tainted food will continue to poison millions each year.

Some large outbreaks have left millions at risk

Since 2018, the federal government has investigated 140 multi-state foodborne illness outbreaks, according to an InvestigateTV analysis of data from the FDA, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the USDA.

When people are sickened by meat, poultry or eggs, the Food Safety and Inspection Service, an arm of the USDA, is responsible. All other foods – from cake mixes to pineapples to walnuts – fall to the FDA.

“What happened was you created the FDA to oversee 80% of the food supply with far fewer resources than USDA has in their inspecting corps,” Marler said. “The Food and Drug Administration, the vast majority of their budget is drugs and their oversight of drugs. Super important. But food safety, and human nutrition, you know, are sort of the redheaded stepchild of the FDA.”

The FDA doesn’t have the resources to inspect every field and every processing plant, Marler said.

Produce has been a particular problem for the FDA. It has been responsible for more than a quarter of the multi-state outbreaks of food poisoning since 2018, InvestigateTV’s analysis shows.

But that percentage could be much higher because, in a third of these large outbreaks, investigators could not determine what product made people sick.

Annette Martin now has a very different relationship with fresh produce after nearly losing her life to E. coli in one of the two contamination outbreaks of Romaine lettuce in 2018.

Not long after eating the salad she washed and prepared for herself, she started to feel ill.

“I started having stomach bug issues,” Martin recalled. “It just got worse and worse.”

She went to see her doctor, who ordered tests. Twelve hours later, “my doctor called my husband and said to get her to the hospital,” Martin said. “She has E. coli.”

Within a few hours, Martin began drifting in and out of consciousness.

“I was starting delirium,” Martin said. “I was having trouble knowing who anybody was... three weeks later, I wake up and I’m sitting in a hospital bed.”

Annette Martin fights for her life in a Louisiana hospital after being sickened by Romaine lettuce contaminated with E. coli. (Jill Riepenhoff/Family photo)

By then state and federal investigators were looking into the outbreak that had stretched into 36 states.

The FDA reported varied levels of sickness in each case. Some people, including Martin, were diagnosed with a potentially life-threatening complication, known as hemolytic uremic syndrome.

“I read the hospital transcript. They had actually talked to my husband Mitch and my son Zack, about putting me on life support,” Martin said. “They both agreed that I would never have that.”

Doctors treated Martin with plasmapheresis treatments and dialysis after her kidneys and organs began failing. She was also given a cocktail of experimental drugs and began to turn the corner.

Once recovered, she turned to Marler for help.

Food safety advocacy born from tainted hamburger

Marler never anticipated that his career would be focused on contaminated food and advocating for food safety reforms.

But then came the case of Jack in the Box. Hundreds of people in California and Washington were sickened by undercooked hamburgers from the fast food chain in 1993.

Seattle attorney Bill Marler became a food safety advocate after representing people sickened by a fastfood chain's hamburgers decades ago. (Jill Riepenhoff/InvestigateTV/Owen Hornstein)

“I got a phone call from a former client of mine who knew somebody who was sick in the hospital with E. coli, which I had no idea what E. coli was,” Marler said. “I filed one of the first lawsuits and then became lead counsel, and there were 700 people sick, and four children died. Nearly 100 children suffered acute kidney failure. It was really the first major foodborne illness outbreak.”

That was a turning point in American history when it came to food safety, Marler said.

“The government stepped in and said, from here on out, you can’t have E. coli in hamburger,” he said.

But, that the outbreak could have been caught and contained much earlier if the state of California had tested for E. coli, Marler said. It had the first cases of Jack in the Box food poisoning but no law requiring that health departments test and report cases. All 50 states now routinely report suspected cases of E. coli to the CDC.

While there have been few E. coli outbreaks tied to ground beef since then, today Marler is particularly concerned about the runoff from cattle farms leeching into water used to irrigate produce. That runoff can be contaminated with E. coli.

“Litigation uncovers facts and compensates my clients, but I can’t force the industry to do the right thing. I can’t force them to stop growing close to cattle feedlots. I can’t force them to, you know, to use a water supply that’s. . .potable water that’s safe to drink,” he said. “Their irrigation water comes from those canals. Those canals run past cattle feedlots. Cattle feedlots put out cattle manure. Cattle manure is where you find this pathogenic E. coli.”

It’s precisely how the lettuce that Annette Martin ate made her ill.

Earlier in May, the FDA announced a new rule that requires annual inspection of water sources for produce – six years after Martin and hundreds of others were sickened by tainted water in a growing field.

Patchy system, little oversight

The deaths of two babies in 2022 from a foodborne illness tied to infant formula shone the light on another problem in the food safety system – a lack of uniformity of which bacteria each state tests for.

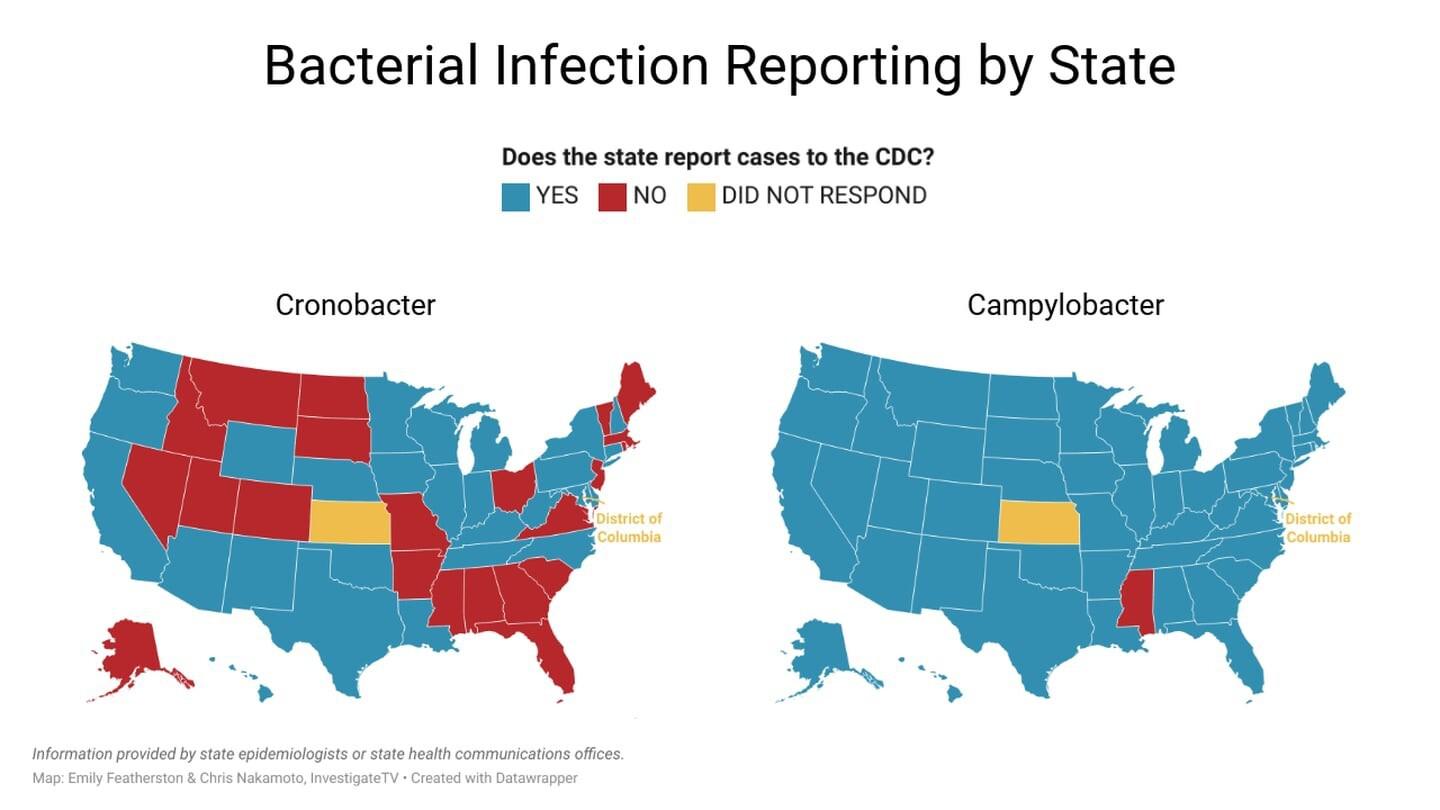

In 2022, at the time of the infant formula outbreak that ultimately sickened four babies, only one state tested for Cronobacter. Earlier this year, the CDC made it a nationally notifiable disease, meaning it’s on a list of about 120 diseases that the federal government wants states to report when cases pop up.

But many states still are not notifying the federal government when cases arise, InvestigateTV has found.

InvestigateTV contacted all 50 states and the District of Columbia and found that, as of early May, 22 states said they do not report cases to the federal government; 27 states said they do; Kansas and the District of Columbia did not respond to our request for information.

Another disease that also has a checkered status of reporting is Campylobacter. “Campy,” as it’s commonly known, is a bacteria that also sickens millions of Americans each year.

It became nationally notifiable in 2015. But Mississippi still does not report cases of Campylobacter to the CDC.

States decide which foodborne infections they report to the federal government. (InvestigateTV)

Analysis of outbreaks shows America’s produce is a high-risk food

Food safety advocates say that Americans need to be vigilant about what they consume, too.

“They need to do their work, their research,” said Morris, from the GAO. “There are some foods that are potentially riskier than others. For example, imported seafood tends to have higher levels of antibiotics in it than wild-caught seafood. So it’s education, right? People have to be informed and make some smart choices based on their lifestyles.”

UCLA Professor and Physician Claire Panosian Dunavan specializes in food safety.

Dr. Claire Panosian Dunavan is a physician and a UCLA professor specializing in food safety. (Jill Riepenhoff/InvestigateTV/Owen Hornstein)

“Leafy greens are definitely a high-risk food,” Dr. Panosian-Dunavan said. “They may be irrigated with water that is contaminated from some upstream cattle feeding operation. Those cattle may be shedding organisms that are antibiotic resistant or in other ways dangerous and the leafy green, of course, there is no kill step. We’re not cooking it.”

Panosian-Dunavan said certain groups are most at risk including those who are elderly, pregnant, and people who are immunosuppressed.

“We’re kind of living in a fools’ paradise,” Panosian-Dunavan said. “Some organisms produce a toxin that can cause a neurologic reaction. Some foods cause an infection in the gastrointestinal tract and then they disseminate like salmonella can disseminate through the blood and to other organs.”

With a renewed outlook on life, Martin said she cannot rely on government action to ensure the safety of what she eats.

Annette Martin now grows her own vegetables and is very cautious about the food she eats after nearly dying from a food borne illness. (Jill Riepenhoff/InvestigateTV/Owen Hornstein)

She credits her faith for helping her survive. She started growing her own vegetables and has completely changed her diet.

“No more salad,” Martin said. “No more medium rare steaks. No more raw oysters. super careful wash all my fruits and vegetables before I eat them,” she said. “If it has, if there’s a chance that it could be dangerous, I cook it if it’s possible to 165 temp.”

Chris is an award-winning investigative reporter with nearly two decades' experience in South Louisiana.

Jill is an investigative producer with decades of experience reporting on health, safety and corruption.