Michigan Live | MLive.com | By Danielle Salisbury | Nov. 7, 2022

In August in an emergency department waiting room, Eboné Colbert remembers going to use the bathroom. So exhausted and dehydrated, she lay on the floor until summoned nurses came to her aid.

“I was just so weak at that time,” said Colbert, 37, of Redford.

Days later, Wendy Lambert’s 5-year-old was heading to the toilet every hour. “It was just awful.”

Despite advice from a doctor to wait and assurances from her husband their daughter was OK, she took Abigail to Michigan Medicine’s C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital in Ann Arbor.

She is grateful she did.

Both Colbert and Abigail were infected by E. coli, a type of bacteria, during an outbreak that began in July and was tied to Wendy’s restaurants, possibly its romaine sandwich lettuce.

Both developed hemolytic uremic syndrome, occurring when small blood vessels in the kidneys become damaged and inflamed and caused by infection with certain strains of E. coli. Though Colbert and Abigail recovered without losing the organs, it can lead to kidney failure.

“I’ve never been that sick,” said Colbert, who spent 12 days at Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak with what she initially feared was COVID-19.

“When I hear E. coli, I’m thinking ‘Oh, you know, diarrhea and throwing up for a day or two.’ But I didn’t know how painful it was, like my stomach.”

Abigail, who lives with her family in Lyon Township, had to have three blood transfusions because her hemoglobin levels dropped. She spent 16 days in the hospital. For all the first week, she would cry out about the ache in her belly. She hated blood draws and wanted always to go home, reported her mother, who found it difficult to leave the room, even briefly.

Lambert, a 44-year-old medical technologist with knowledge of potential complications, would encourage her, try her best to be positive, tell Abigail she was going to get through it. “And then I’d like go in the bathroom and have my little meltdown.”

The Lambert family and Colbert are now seeking legal redress.

Colbert and her lawyers are suing Wendy’s, the Rochester Hills owner of the Farmington franchise where she ate, and whatever corporation, not yet known, manufactured, distributed, imported, packaged, or grew the illness-causing product. Her case is pending in Oakland County Circuit Court.

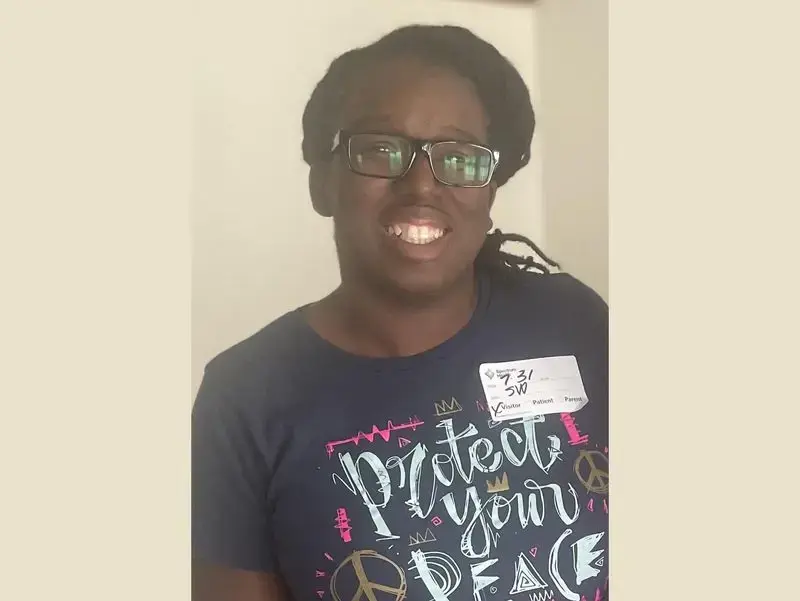

Ebonē Colbert, 37, of Redford spent 12 days at Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak with an E. coli infection that led to a kidney complication. She had eaten days earlier with her son at a Wendy’s restaurant.

The lawsuit is one of at least three in Michigan stemming from a summer outbreak, and there could be more. The Lambert family’s case has not been formally filed.

Colbert’s lawyer, Bill Marler, based in Washington and focused exclusively on food safety cases, is representing the Lambert family and several others, including Zachary Nitz.

Nitz contracted an E. coli infection allegedly after he ate a Big Bacon Classic Aug. 6 from a Wendy’s at 2333 28th St. SE in Grand Rapids. Nitz also sued Wendy’s, the franchise owner and the unknown product provider. His lawsuit is pending in Kent County Circuit Court.

Attempts to interview lawyers representing the franchises and Wendy’s corporate communications were not successful. Messages left for the franchise owners did not elicit responses.

A total of 109 people from six states, including New York, Kentucky, Ohio and Pennsylvania, were known to be infected from July 26 to Aug. 17. Michigan had the greatest number of cases with 67.

Ill people ranged from age 1 to 94. At least 52 were hospitalized and 13 developed hemolytic uremic syndrome. No one died, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. By Oct. 4, the outbreak had concluded.

Jamie Core, 37 and then living in Allendale, did not develop the syndrome, but he was miserable nonetheless. Ill with E. coli infection in late August, he could hardly get out of bed. He didn’t yet know what was wrong. He couldn’t control his body.

“Depression kicked in. I would just sit there and cry.”

Core and his husband have a contractor business. He was too sick to work for weeks and Eric Core took care of him. They lost one job and were still catching up on others.

Jamie Core, also represented by Marler, went twice to Wendy’s, eating a chicken sandwich and a burger, while traveling from Michigan to Chicago for a five-day birthday trip. He started to feel terrible within days of their return.

“I’ll never eat at Wendy’s again, honestly.”

Of 82 people with a detailed food history, 68 reported eating at Wendy’s in the week before their illness began.

The CDC said it had not confirmed the outbreak source, but many sick people reported eating sandwiches with romaine lettuce, and Wendy’s then removed from their sandwiches the leafy green, linked to several past outbreaks, often because livestock fecal matter can get into irrigation systems.

Colbert on July 27 had a Wendy’s single when she and her son, 4, stopped as they always did after his Wednesday gymnastics class. Her son had chicken nuggets and remained healthy.

Abigail Lambert works on a coloring book at her home in Wixom on October 20, 2022. Abigail was exposed to E.coli during the outbreak in July and August linked to Wendy’s restaurants and was hospitalized for 16 days.

Lambert said her daughter had chicken nuggets, fries and milk while she had a burger. She picked off the onions and pickles and Abigail ate the onion.

They didn’t eat lettuce, but that doesn’t mean a leafy green wasn’t the culprit.

E. coli has a “very low infectious dose,” meaning it takes less than 100 bacterial cells to cause disease after ingestion. Contamination could spread, especially if the bacterial concentration on the lettuce was high, said Shannon Manning, Michigan State University professor in the Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics.

Because leafy greens grow low to the ground, they may be more readily contaminated than other types of produce, Manning wrote in an email. They also are eaten raw instead of cooked. Even washing before consumption might not be sufficient because the pathogen is capable of entering the leaf pores.

Marler, the Washington lawyer, wants to determine: Where was the product harvested and why was it contaminated?

He fears he will learn, as he has in past cases, lettuce was grown “near a bunch of cows,” and laments the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not done more.

The FDA has called livestock a “persistent reservoir” of E. coli and urged famers to be aware of “adjacent land use practices.”

In November and December 2019, for example, 188 people were sickened with E. coli in three outbreaks connected with consuming leafy greens from California. An outbreak strain was detected in a fecal-soil composite sample taken from a cattle grate less than two miles upslope from a produce farm, according to the FDA.

Chains like McDonald’s, Wendy’s and Chipotle and grocers like Walmart and Costco can pressure suppliers to “clean up their acts,” Marler said. “These big, multibillion dollar companies have an obligation to protect their customers.”

Wendy’s needs to be held responsible, Core said.

Lambert said for her family, it is not about the money. “I’m just tired of hearing about toys getting recalled and people getting sick from foodborne illnesses. And I’m tired of big corporations just like sweeping stuff under the rug, and ‘Oops, no big deal.’”

Abigail is in kindergarten. Laboratory results looked good. as of mid-October, and she was eating normally. “But we are also worried about the stuff that you can’t see… because she was so sick.”

She will have to forever watch her blood pressure and is predisposed to kidney infection; her embattled kidneys could be less capable of fending off any subsequent trouble.

The first day of school, tasked with illustrating her feelings, Abigail drew a picture of a girl with two tears and a red line coming from her arm. “That’s the blood,” she explained.

Colbert, a communicable disease investigator for the state of Michigan, was off work for five weeks, not all of it paid.

She was away from her son. She had no idea when she would go home, and worried about money.

Beyond recovering those financial losses, she too wants to see change in food safety practices. “I don’t want anyone else going through that, and I’m an adult. I can only imagine having a child go through that, when it is not necessary.”

‘Never saw it coming’: Ohio child’s kidneys nearly failed due to Wendy’s E. coli outbreak

Max Filby of The Columbus Dispatch

Brittney Tebay never imagined eating at a fast-food restaurant could land her child in the hospital, but that’s exactly what happened.

Her son Carter, who was 9 at the time, ate at a Wendy’s on Aug. 5, and by Aug. 9 the Toledo-area boy was vomiting and dealing with bouts of diarrhea.

After multiple visits to two Toledo hospitals, a doctor told Tebay that she needed to get her son to Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus. Carter was suffering from a severe bout of toxic E. coli and his kidneys were failing.

“I never saw it coming,” Tebay said. “You see that kind of stuff on the news, but I never knew that E. coli could cause kidney failure.”

At least 52 people were hospitalized during the outbreak, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No one is thought to have died as a result of the outbreak, which ended in early October.

Carter was one of at least 24 Ohioans and 109 Americans sickened across six states in an E. coli outbreak that began in late July and was linked to Dublin-based Wendy’s.

E. coli is the name of a broad category of bacteria largely considered harmless. But some strains of E. coli produce a toxin called Shiga. These Shiga toxin-producing E. coli live in the intestines of many animals and are usually transmitted to people through contaminated food, according to the CDC.

While most people recover from an E. coli infection in about a week, not everyone does. The CDC estimates around 265,000 Americans are infected with toxic E. coli every year, and 30 people in the U.S. die from the bacteria annually.

Although serious illness is rare, it’s possible, said Jiyoung Lee, a professor of environmental health at Ohio State University’s College of Public Health. Young children, the elderly and people with weakened immune systems are the most likely to suffer from serious illness due to E. coli, Lee said.

People often start feeling the effects of toxic E. coli three to four days after ingesting it, according to the CDC. Symptoms can include stomach cramps, vomiting, bloody diarrhea, fever or even the early stages of kidney failure, like what Carter experienced. “The possibility is always there,” Lee said. “Once it happens, it can be dangerous.”

How the Wendy’s outbreak unfolded

More than 80% of people sickened in the outbreak told public health officials they ate at Wendy’s restaurants in Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Kentucky, Pennsylvania or New York. But it’s unclear just what caused the E. coli outbreak.

Many ate burgers and sandwiches with romaine lettuce. As a precaution, on Aug. 19, Wendy’s removed the romaine lettuce being used in burgers and sandwiches at restaurants in states where sick people ate.

When asked to comment, a spokesperson for a public relations firm representing Wendy’s referred The Dispatch to a prepared statement from the food chain stating that it was pleased no more cases had been reported as of Oct. 5.

“As a Company, we remain committed to upholding our high standards of food safety and quality,” the statement read.

The outbreak linked to Wendy’s is one of 19 investigated by the CDC across the U.S. since the start of 2018. That marks an uptick from the 11 outbreaks investigated during the previous five years from 2013 through 2017, according to the CDC.

If the outbreak was caused by lettuce used at certain Wendy’s locations, it could have infected people who didn’t eat something with that specific ingredient. Anything prepared in the same space as food carrying toxic E. coli could become contaminated, Lee said.

Every outbreak is an opportunity to inform people of the importance of safe food preparation and the need to wash leafy greens and other produce, Lee said. That includes produce labeled as washed or ready to eat, Lee said.

“I never eat directly from the package without washing (produce) first,” Lee said. “A majority of people think it’s common sense but it isn’t. I think we have to remind people more. … We have to increase awareness.”

When an outbreak occurs, attorney Bill Marler usually has his eye on it.

A lawyer at Marler-Clark, the self-proclaimed “food safety law firm” in Seattle, Marler is representing multiple plaintiffs, including the Tebay family, in lawsuits against Wendy’s due to E. coli. Marler has represented victims of foodborne illnesses since 1993.

Although prevention efforts are worthwhile, Marler said that more needs to be done to stop E. coli from contaminating food at the source.

When it comes to leafy greens, the main issue is that lettuce farms often are located too close to livestock pastures and feeding areas. Sometimes, Marler said, they’re so close that the lettuce and the livestock share the same water source, and so manure containing E. coli can get into the water used to sustain lettuce and other produce.

Until something is done to better regulate the issue, Marler said the problem will continue.

“Everybody has known that,” Marler said. “Every time there’s a major outbreak everyone throws their hands in the air and says, ‘Oh my god, we’ve got to fix this’ and then ultimately they never do it.”

While Marler said the number of food recalls seems to have grown, he said that’s actually a positive development. Periodically testing food and issuing recalls is the best way to prevent outbreaks of food-borne illnesses, he said.

Columbus-based Jeni’s Splendid Ice Creams is one example that Marler cited as a company that’s done a good job at preventing outbreaks. Jeni’s recalled all of its ice cream pints and temporarily closed all of its scoop shops in April 2015 after a random inspection detected the presence of listeria in an ice cream sample taken at a Whole Foods store in Nebraska.

“Recalls can be a really good thing,” Marler said. “If you see a recall, you should feel like the system’s actually working.”

Fearing ‘the worst’

Despite suffering a severe case of E. coli, Carter was one of the lucky ones.

After about two weeks at Nationwide Children’s, Tebay said her son was healthy enough to return home to Sylvania, a suburb of Toledo. He’s expected to make a full recovery.

“It was scary,” she said. “I never let myself think the worst, but I was scared we were going to be dealing with dialysis for a good chunk of his life, if not forever.”

Still, the ordeal had an impact on Carter and his mom.

The two were in the car together recently when a Wendy’s ad came on the radio. Carter asked his mom to change the station or turn it off. It’s unlikely they’ll ever eat at a Wendy’s again, she said.

In fact, she said the experience has made Carter skeptical of other food and restaurants. The two recently ate at a McDonald’s restaurant and afterward Carter worried that his burger tasted off.

That paranoia can only be attributed to his battle with E. coli, his mother said.

“We’ll always be more leery of going out to eat now,” she added. “It’s not just me saying that. My son is scared.”